The Hidden Fight over Women’s Work (New Labor Forum)

From an article in New Labor Forum, vol. 29, issue #1, 2020 by Jenny Brown

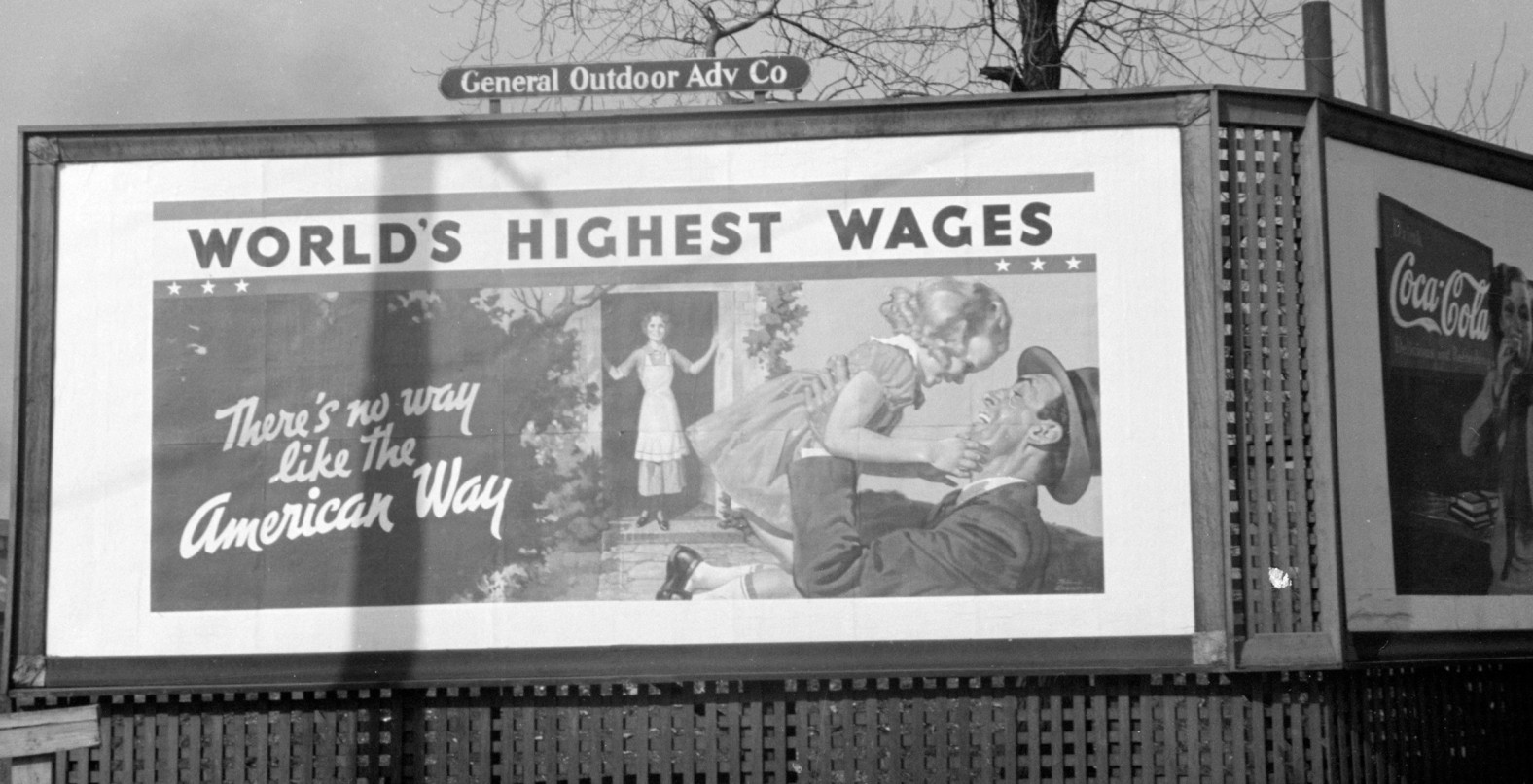

The U.S. birth rate is now the lowest it has ever been. Other countries, confronting low birth rates in the twentieth century, instituted supports to make raising children more appealing. They provided universal child care, health care, paid leave, child allowances, and shorter working hours. The United States, by contrast, has taken the low-cost route to raising new generations: poor access to birth control and abortion. But despite these obstacles, women are refusing. This article will explore what it would take for working people in the United States—and women in particular—to leverage our spontaneous birth slowdown into family-supporting policies.

This article will explore what it would take for working people in the United States—and women in particular—to leverage our spontaneous birth slowdown into family-supporting policies.

Starting in the 1980s, while birth rates in most developed countries dropped, U.S. rates remained elevated. We had higher teen pregnancy rates, and higher unintended birth rates, about twice those of Sweden and France.1 But more recently, the U.S. rate has declined, across ethnic groups, and is now considerably below the 2.1 “replacement rate” required for a stable population, reaching 1.72 in 2018 (see figure on following page). The women’s liberation group Redstockings in 2001 described this as a “birth strike,” a reaction to the difficult conditions women face having and raising children.2

Surveys indicate that potential parents are deterred by the costs of child care and housing, long or irregular work hours, low wages, unreliable health care, and student debt.3 In National Women’s Liberation (for which I am an organizer), women name these factors as reasons to stop at one child or have none at all. In consciousness-raising meetings, testifiers describe the stress and exhaustion of their “double day”—eight or more hours of paid work and then an additional eight hours a day of unpaid care work and housework. Others recount difficulty finding partners who are willing to take the plunge into parenthood, wary of the time commitment and costs. Some say they were deterred by memories of their mothers’ struggle to raise them.

As in other countries with modest birth rates, government and corporate planners from both sides of the aisle would like the U.S. birth rate to be higher. “Simply put, companies are running out of workers, customers or both,” the Wall Street Journal claimed in 2015. “In either case, economic growth suffers.”4

“Declining birth rates constitute a problem for the survival and security of nations . . . in the broadest existential sense of national security,” wrote Steven Philip Kramer of the National Defense University in his 2014 book, The Other Population Crisis: What Governments Can Do about Falling Birth Rates. “For several hundred years, economic growth has been tied to prosperity . . . Growth in population has increased the size of the domestic market and labor force.” While many scholars continue to worry about the effect on the environment of expanding global populations, in fact birth rates are now dropping in most of the world and total population is expected to be stable or declining by 2100. Among continents, Europe, Asia, North and South America are expected to have less population in 2100 than in 2050. Only Africa is expected to grow.5

Data from Jay Weinstein and Vijayan K. Pillai, Demography: The Science of Population (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016), 208, and National Center for Health Statistics Births, Final Data for 2016.

READ the rest in New Labor Forum.